Messaging Basics with the Outbox Pattern

If you want to develop a modularized system, which is distributed (or you want to be prepared for that), that “just publish an event” opens the door to some of the most complex problems in software engineering. This post will demonstrate that and will show you how those problems can be solved. It’s done by pseudo C# code using MediatR.

A practical, basic Todo example

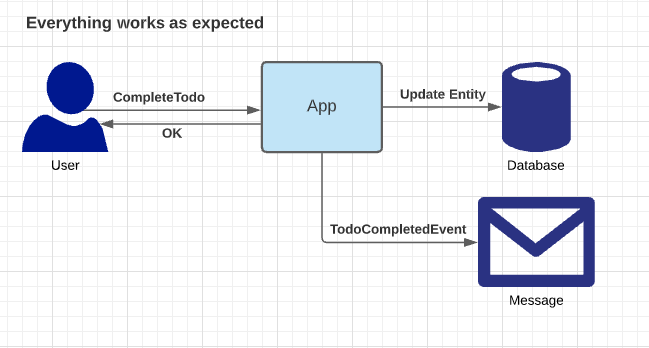

Let’s imagine we need to react when a user completes a todo. We decided to implement it with an event — and even we currently have only a single deployment unit, we want to be prepared for high scalability. In the future, we may split deployment units and integrate them via Message Bus.

Let’s view some of the application code:

public class CompleteTodoItem

{

public class Command : IRequest

{

public Guid Id { get; set; }

}

public class Handler : AsyncRequestHandler<Command>

{

private readonly DbContext _dbContext;

private readonly EventPublisher _eventPublisher;

public Handler(DbContext repository, EventPublisher eventPublisher)

{

_dbContext = repository;

_eventPublisher = eventPublisher;

}

protected override async Task Handle(Command request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var item = await _dbContext.TodoItems.FindOrDefaultAsync(request.Id);

if (item == null)

return;

item.Complete();

await _dbContext.SaveChangesAsync();

_eventPublisher.PublishAsync(new TodoCompletedEvent(item.Id));

}

}

}

Very simple. And I really hope you spotted the obvious issue here.

Murphy

I’m sure you know Murphy’s Law: “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong”. So let’s inspect our solution and find out what can go wrong.

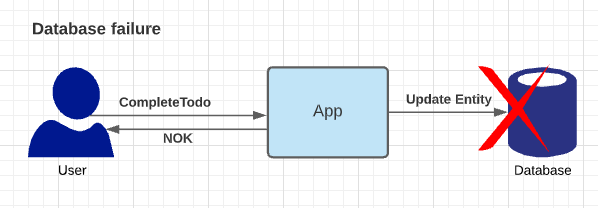

One thing that can go wrong is, that the database becomes unavailable. And while you may think “it happens so rarely” — it will go wrong in a distributed system.

This problem is not an issue with the actual implementation. If we fail to commit the transaction to the Database (by calling SaveChangesAsync()), we will also fail to publish the event. We can catch the Exception and inform the user — easy.

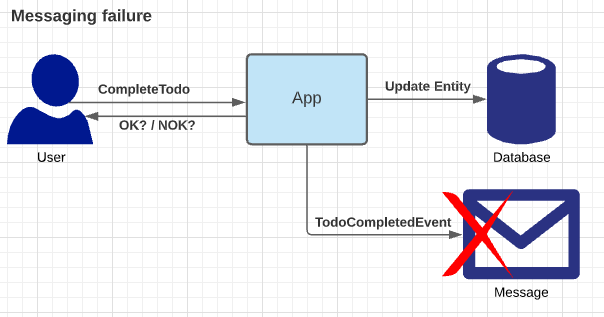

Another thing that can go wrong is, that our messaging infrastructure becomes unavailable.

This problem is an issue with our actual implementation. If we successfully commit the transaction but then fail when sending the event — we updated the entity state in our application but every downstream system which reacts to the event will have an invalid state.

“Just commit the transaction after the event is published”

Without any deeper investigation, you might try that one out. But it won’t help. Let’s try and analyze:

public class CompleteTodoItem

{

public class Command : IRequest

{

public Guid Id { get; set; }

}

public class Handler : AsyncRequestHandler<Command>

{

private readonly DbContext _dbContext;

private readonly EventPublisher _eventPublisher;

public Handler(DbContext repository, EventPublisher eventPublisher)

{

_dbContext = repository;

_eventPublisher = eventPublisher;

}

protected override async Task Handle(Command request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var item = await _dbContext.TodoItems.FindOrDefaultAsync(request.Id);

if (item == null)

return;

item.Complete();

_eventPublisher.PublishAsync(new TodoCompletedEvent(item.Id));

await _dbContext.SaveChangesAsync();

}

}

}

With this solution, we fixed one problem. If our messaging infrastructure becomes unavailable, we won’t commit the transaction and will have a valid state. But if we can’t commit the transaction the event has already been sent. This is also critical if you have some constraints which only reside on your database — then we send an event for something which is invalid!

If we dig deeper, we realize we will always have such a problem when we are writing to two resources which has no common transaction support across those resources.

Outbox Pattern to the rescue

Luckily, we aren’t the only ones with such problems — and there are solutions for that. A quite “easy” way to solve such problems is to implement the Outbox Pattern. But you will see, even implementing such a relatively easy pattern will increase your “just publish an event” problem’s complexity.

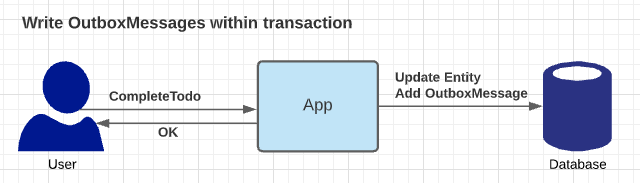

You can imagine the outbox pattern the same way your E-Mail client works. If you send an E-Mail and currently are disconnected from the internet, it will go into the “outbox” folder. As soon as you are reconnected it will be sent. We can also use this approach in our use case. Because we have to “store” the event somewhere and we know we must be consistent with the database transaction we can store our events in the database. Lets’ see how that looks like:

That way, we have our event inside our database as an “OutboxMessage”. The OutboxMessage is inserted within an atomic transaction together with the entity — easy. Our code looks like that:

public class CompleteTodoItem

{

public class Command : IRequest

{

public Guid Id { get; set; }

}

public class Handler : AsyncRequestHandler<Command>

{

private readonly DbContext _dbContext;

public Handler(DbContext repository)

{

_dbContext = repository;

}

protected override async Task Handle(Command request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var item = await _dbContext.TodoItems.FindOrDefaultAsync(request.Id);

if (item == null)

return;

item.Complete();

_dbContext.OutboxMessages.AddAsync(new OutboxMessage(new TodoCompletedEvent(item.id)));

await _dbContext.SaveChangesAsync();

}

}

}

This is all good, but we haven’t published our event yet — the only thing we ensured is, that the event in the OutboxMessages table of the database reflects the committed state of the entity. Now we should think about when and where we should read those OutboxMessages and finally publish the event to the messaging infrastructure.

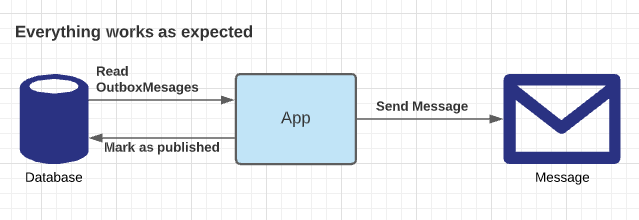

If you think again about your E-Mail outbox, then the message is removed from there as soon as it was successfully sent. We have to do the same here. After we successfully published the event to the messaging infrastructure, we need to either delete the OutboxMessage or mark it as published.

But wait — we have the same problem here as before, right? Our good Friend Murphy will hit us again. We have to deal with database and messaging failures once again.

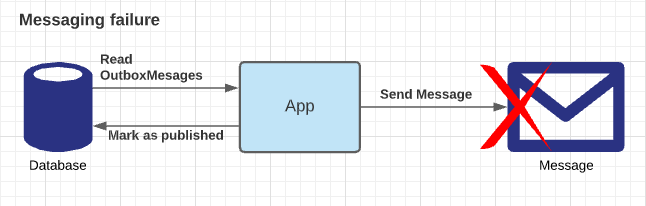

What happens if our messaging infrastructure fails to send the message? It will still stay “unpublished” in the database. This is not really a problem, we just need to check the outbox periodically — maybe in a background job. It’s the same way your E-Mail client does it, right? Problem solved — easy. Now let’s look at the database failure problem:

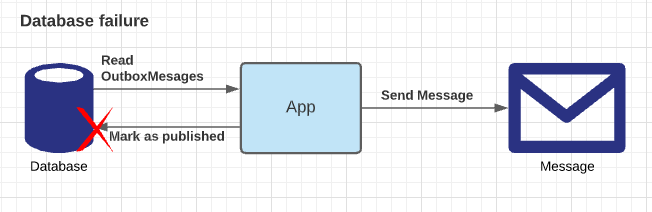

If we sent the message successfully but fail to mark it as published in the database, what happens? Well, our background job will get triggered again and the message will be sent once again. Have you ever heard of the “at least once” semantic? Well, that’s exactly the case. We are sure that the message is sent (sometimes) but we can’t ensure it’s only sent once.

The fact, that we can’t be sure the message is sent immediately will lead our system towards an eventual consistent solution where it is consistent, just not immediately. The fact that a message is sent multiple times is not a problem for us right? It’s the problem of the message consumer.

While there are patterns for message consumers (deduplication), we can help them a lot by making our messages idempotent. “TodoItemCompletedEvent” is idempotent because semantics of it contains the state. If we would publish a “ToggleTodoItemEvent” this would not be the case. If the event gets sent twice, it would not reflect the current state. Then, our downstream consumer will need to implement deduplication (identify already consumed messages) in order to update its internal state correctly.

Conclusion

As you have seen, “just publish an event” is only easy in the absence of Murphy. While starting with a really basic example, in the end, we touched on buzzwords like “eventual consistency”, “idempotency” and “deduplication”. You can go and implement an outbox by yourself (I will show a basic implementation in an upcoming post), or you just use a framework that cares about all that stuff. My personal favorite is NServiceBus.